“I had grown up in an environment where a lot of us as Black people were taught to hate ourselves. To survive we had to make ourselves be the butt of the joke.”

Gamal Turawa became the first Black police officer to openly admit his sexual orientation. Although he was relieved, he says he had to make fun of his skin color to survive.

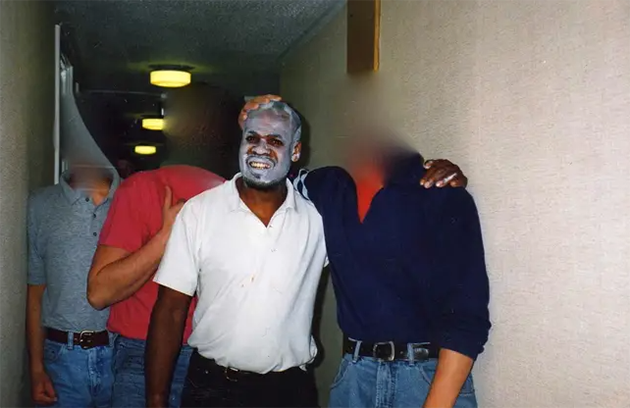

Jokingly he told that his fingers looked like Kit Kat and that allowed others to paint his face whiter to become part of the group and be like them.

At the time it was conceived as a joke but it was a way of being accepted.

Gamal previously had other bad experiences with police officers. A cop scoffed at him as he was handing a coin to a white boy. In this way, he had seen the world for many years.

“I grew up in the time when Lenny Henry was on The Black and White Minstrel Show,” he said. “Where you would regularly hear about Black kids who were trying to jump into a bath of bleach to try and make their skin white or try to scrub the blackness off the skin, or take talcum powder and make themselves look white,” he said.

Gamal grew up in a white foster family and learned there that the white color face is the face of success.

Another meeting that impressed him was when he saw a black-skinned traffic policeman. “It was the first Black person I’d seen who stood with confidence,” he said.

“I remember watching him putting his hand up to stop the traffic and this shiver just went through me, so I think the seed was kind of planted there but it was not something I was conscious of until years later,” he explained.

He joined the police in 1960. He remembers that white colleges mocked him for his skin color. He says he allowed it because “Life isn’t so clear and so defined,” he says. “This stuff is messy. It’s confusing. It does not follow any logical process,” he said.

Gamal says many people loved him and shook his hand while others hated him. This hatred was further heightened when his sexual orientation became known.

He experienced homophobia from his family, but it seemed to him that becoming a police officer was his haven.

In 2018 he left the police to focus on telling his story to officers in police forces and other organizations, becoming a ‘facilitator for courageous conversations.